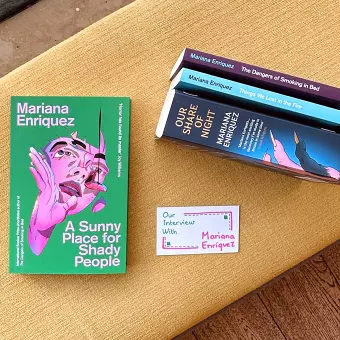

An Interview with Mariana Enríquez

To celebrate the publication of her latest short story collection A Sunny Place for Shady People, we got the chance to chat with renowned writer Mariana Enríquez. We're big fans of her writing at the bookshop so we couldn't wait to discuss this haunting new collection along with her previous work including Our Share of Night, The Dangers of Smoking in Bed and Things We Lost in the Fire.

We gathered questions from the team, and our bookseller Selena sat down with Mariana to discuss a wide range of topics including her sources of inspiration, the true crime genre, the socio-political climate in Argentina and her writing process. Thank you to Mariana for the wonderful conversation and to Granta for the opportunity!

You can purchase a copy of A Sunny Place for Shady People here.

Q: The use of body horror seems to be more prevalent in this collection than in previous ones. Was there any reason or significance behind this?

A: Yes. I think, obviously, when you start writing, you don't really think about it. It just comes or at least I don't have a plan. I let it happen and it happened. And then when I finished it, I noticed it. The people that already notice it, and I think it has to do with, two things. The first one is very personal - that has to do with my age. I'm 50. And, at this age, the body of women changes. I don't mean exactly that the changes are horrific. The changes are the changes. The feeling is pretty scary. It's pretty sinister. Sinister in the sense that you don't recognize your body anymore. Your body is doing things that it didn't used to do, it wasn't supposed to do, and there's very little information about this stage of women's lives and bodies. Like, even doctors don't tell you that much about what it is to go into perimenopause and stuff. So one day you wake up, like, feeling absolutely out of your body and out of your mind and you think there's something wrong with you and it's just the way it's supposed to be and I think that happened. So to me, it was like a second time in my life that I felt like that. So I think the first was teenagehood. And as a teenager, it's like everything is changing and now everything is changing again. And it's pretty lonely, so there's a lot of that.

And then I think the other thing was clearly the pandemic even if I wasn't writing at all about the pandemic. I think those years were years where the body and sickness and death and what could happen to the body were very felt nearer. And also there was a lot of explicit language. Like, we really knew what was going on with your body and if you got this and the pneumonia and people, you know, and it was like a whole full on experience on how the body gets sick and dies non stop on every media for at least a year solid. That's a lot. And even if you don't really want to talk about it explicitly, it's there somehow. That's really interesting.

Q: How did you find out about the tragedy of Eliza Lam, and what drew you to creating a story around it?

A: I think at the time when it happened, I just read it in the news. Like, it wasn't of course, in Argentina, it wasn't big news, but it was somewhere. And I find that area of LA very fascinating because it's downtown, you know, where they give you the Oscars, the stars are on the street, and it's very rough, like, very rough. And the hotels from the 1920s, 1930s are art nouveau and extremely delicate and beautiful on the outside. And then you enter and it's like, wow - very rough. And you know, things don't really impress me, but this is like what? Especially because it's like a mask. It's not something. And then when you enter it's very sinister. And now with all the people living in the street and, I mean, the homelessness and the inequality of that city is just out of control.

And, and of course, that particular hotel was a haunt for serial killers. It's just a crazy place. And also there's a weird serendipity with the case of Elisa. There's a horror story that comes from the early nineties, much before this happened, by a Japanese writer called Koji Suzuki (Suzuki is the author of The Ring), and he wrote this short story or novella where a girl drowns in a tank. And then they made a movie out of it with Jennifer Connelly. But the thing that was exactly the same was that people drank her. So that was a bit to me like an incorporation of her. What happens when you eat another person's flesh? Because that's what happened - it was very disgusting. And at the same time, very sad because nobody noticed and she was alone. And then it's that video that is on YouTube that really there's no legal way of taking it down, even if you're the family, because it keeps replicating. And it's very sad because it's her last moments on TV on the CCTV of the elevator. She's clearly having a crisis of some sort, and that's our last image of this young woman that was basically sick and alone in a hotel. And it's so sad and at the same time, so creepy. So, of course, it was going to be something that really attracted me as material because it had many things that interested me like young women, body horror in a way, solitude, mental health, ruined places. And to me, that video is very wrong and very haunting and the fact that it's like a ghost on the Internet. So I really wanted to explore laws and ghosts with another story that involves the real one.

Q: Do you draw any inspiration from horror films when writing? And if so, do you have a favourite or ones that you're drawn to?

A: I do. I think in writing in literature, I can be very naive. I'm very surprised, but still I can, not even consciously, know what the writer is doing and get bored because you know the mechanism. But in movies somehow, even if I don't like them, because there are lots of bad movies, especially in horror, there's a point when I just get sucked in. When the movie is very bad, I kind of wake up from a dream. I really like David Lynch - to me, he's a horror director and he really scares me. And then I can get images from movies sometimes, not a particular director or a particular style, but images here and there of movies that are not very scary overall. Let's say, in a movie like Pearl, which I really liked, the scene that was absolutely in my head was when she goes to the scarecrow and kind of embraces him and kisses him. That was tremendously creepy, very, very sexy, and very disturbing. And it's that scene that is in my head, and somehow, one day, it's going to come out. But this idea of a lonely woman and the only thing that she can embrace in a way is this dead piece of wood in the middle of nowhere. It's very striking. And maybe they don't even know sometimes because it’s very difficult to make scary images. It's the things that are not really scary in itself, but when you see them, they have a lot of meaning. And that happens to me most of the time. Sometimes the plot is very silly, but there is something there. Maybe it gives you a lesson in some other ways, to get the image right. Because that's important. People have to be scared. It can be generic. It has to be very specific.

Q: Have you ever wanted to return to a story that you've written and expand on it?

A: Not really. It only happened once with a story in my second book of short stories, Adela's house that ended up in the novel. It was purely accidental because I was writing a novel and I needed a house that did certain things. I was going for a lot of sinister architecture, buildings that were creepy. I find that very interesting. Especially in places like here when you don't have that much history. It's very topical to do a haunted castle, but that doesn't work for me. And some suburban houses when they are abandoned or run down that have not so much history, but probably a history of misery of the family that lived there and that they are like an example of lives that are small. So I was looking for that metaphor of a house that seemed very, very small, like a mask. Like the hotels in LA, but the other way around. It looked very normal, but inside it's bigger, but it's also bigger psychologically because what happened there, it's much more important than the house itself. So I needed that and the house that did that was very precise. It was eating people. So in the sense that you go in and you don't go out. And I realised I have reached that house, so I put the house in the novel and it became a whole other thing. But in general, I’m very finished with the short stories.

Q: Are there any books or authors that before you began writing inspired you to tell stories?

A: Many. The short stories of Julio Cortázar - he’s a fantastic writer, but very adult. I think it was the first one that I read in Spanish and in Argentinian, (I mean, with our own streets etc.) that wrote about things of the city that were scary. Sometimes with short story authors of the horror or fantasy genre, they get relegated to writing juvenile literature. To me it’s very important and serious to write for young people. It’s good for young people to open their minds, but it’s certainly not the intention of the author, especially with the things that they're dealing with like abuse. And there are many of his stories that I read when I was younger that I didn’t understand, but I liked them.

And then, of course, there’s Borges, kind of a national figure - he’s very interesting. And they are both short story writers. We don’t really have a tradition of a novel, we do, but it’s not really the same as other places. I guess that’s why there are many short story writers here.

And then, when I was little, I loved the Brontë sisters, the 3 of them. Especially Emily because she’s the crazier one. And I read a lot of British and American literature - like J.G. Ballard and Ray Bradbury.

I read a lot of, and still read a lot of, graphic novels like Alan Moore, Garth Ennis and all the Vertigo people of the nineties. Then I was reading a lot of manga and Stephen King, obviously. So it was a mix of things when I was young.

Q: What is it like writing a short story compared to a novel? And do you have a preference?

A: I prefer novels, but they are more difficult and they take more time. Other people will tell you that short stories are more difficult, but I think it's all a question of what you've been raised with, as in reading and also, your first institutional reads in school. I started reading short stories in school because that’s our tradition. So for me, the short form comes very easily. And, to me, the short story is about an image or an idea. I see some of the ideas we were talking about, like a house that has some secret and you can tell because of this and that. And that house somehow represents whatever in my country it could be, from places where things happen during the dictatorship or anything. But something in particular. And that usually is a short story. And I write them quite fast, like, in a week or something. Then you can correct them forever if you want, but the writing is very like a song - quick. But a novel to me are characters that start to appear, these characters are very fleshy, are very like people. And I think about them. I imagine situations and make a world around them. That is how I know that it’s a novel because this is not about plot. It's not about symbols. It's not about metaphors. It's about the lives of these people and what they are doing. And, when that happens, I really like it. I really like the process, but for me it's a difficult process. There's people that can make a novel a year. For me, it takes a lot because first, I have to write it in my head. And I spend a lot of time with these people, and I look for things. Building the world is very slow, it’s a process of years. So I like novels more, but I wish the process would be shorter because it’s kind of a lot of work.

Q: I found the stories in this collection to be particularly moving and felt myself wanting to sit with them for a while after finishing. How do you balance the truly deplorable and frightening elements while also leaving room for the reader to feel empathy?

A: I kind of believe that terrible things happen in reality all the time. Well, reality is a philosophical concept, but let's say in our lives all the time. And I think all I do when I write horror is magnify them in some cases. In other cases, not really. For example, there's a short story in this collection called Face of Disgrace that is a generational family where all the women had been raped. And to me, the scary thing there is the silence. And that happens not only in families, but between women that are just friends - it's very difficult to talk about. Sometimes, this island is imposed by cultural circumstances, but sometimes it's just a silence that comes with a trauma that you don't want to talk about. And that kind of becomes the monster in the room, that silence in itself. So out of that silence, I built the character of this rapist without a face. That also was like an urban legend in that a writer told me that there was a legend in her small town of a man without a face that was attacking women.

Then, for some reason, I was talking to another friend of mine who had a hallucination of a boy that was ringing her doorbell and then when she opened the door, she saw that he didn’t have a face. And so I said, this is a pattern, there’s something here. And that got me thinking a lot about silence. So I think that’s a way to build empathy, to start from something real. And from that, build it up to accentuate the horrific aspects of everyday things that we are kind of used to or take for granted. It’s not something that I think about before, but something that happens and then when I correct it and analyse it, I try to balance. There’s the human part, the women suffering that is the kind of emphasis. And then sometimes, the other part, the horrific, has to be louder. For whatever reason, sometimes even for fun. But in general, I try to start something real, that affects people’s lives.

Q: You've been vocal about how the history and contemporary landscape of Argentina is woven into your stories. What do you think it is about writing within the horror genre that particularly lends itself to sociopolitical commentary?

A: Living in South America in general, and in Argentina in particular, there are elements of growing up and political history that are really phantasmagoric in itself. Like especially the idea of the haunting of history. In the seventies and early eighties there was the last dictatorship (when I grew up) and 30,000 people disappeared. This wasn’t the same as being killed because there were no bodies and no explanation. There's a pact of silence between the people that committed these crimes - that is very creepy. Because in any organisation after 40 years, somebody cracks. Somebody for whatever reason, because he's tired, because he's old, because he went to jail because he wants to get out of jail and get a better deal or whatever, and there's something very perverse about them not saying anything. There's children of these people that were killed that never knew anything about their parents. But these are people of my age - that didn't happen to me or to my family. I'm the family of the orphans. And so your immediate adults were basically killed, not there, or in the case of many others, were very disturbed because they were traumatised.

And then the economic crisis being always the same really seems like a curse. I don’t think it’s casual that there's so many people from South America writing dark fiction in general because everyday life itself is kind of nightmarish. I have a reasonable life and most of us do, but if you're a bit open to what's going on around, it’s pretty horrific.

And in all different ways, like, if you go north with the crisis with drugs and stuff. The horrendous violence that that brought just for pleasure and sometimes not even for the pleasure of the people in those countries, but, to export that to the northern hemisphere, it's all very nightmarish. And it feels like that in a way because sometimes the stories are so incredibly big. Like they found a common grave with 500 bodies and nobody knows who they are.They killed the entire family, nobody asked about them and this is everyday life in Mexico.

So there's a lot of aspects of everyday life that are horrific and they have the structure of horror fiction. So, really, it's a genre that applies to social commentary because it has the same structure, the same contents and the same characters. And, that's very unfortunate when there's all this other reality that is not bad. We are countries that are very, very communitary, very fun, and very beautiful. People are very nice and open and, you know, there's all kinds of things here that are brilliant. But the people, me or other writers, that are interested in the dark side of things, they're very near. So, I mean horror just works as social commentary. I'm really glad in a way because it's a genre I really love, but I'm very interested in talking about sociopolitical issues. And to be able to mix them without making it something that you have to stick together because it's forced, but it sounds very natural. And I'm very glad that I can express myself in this genre and talk about the things that I'm interested in.

Q: What does your research look like when drawing on urban myths and the supernatural?

I do it in everyday life, not specifically, but it's like a hobby. For example, this is in Catalan, but I have this book L'Emporda Mitic: Llegendes. It’s the mythic of L’Emporda (L’Emporda is in Costa Brava), and then Llegendes which means legends. I just got this because I am interested in it and I will probably write something, but not a short story, more like a guide of the area or something like that because they found out that I am interested in it. So yeah, it’s kind of a hobby, I listen to podcasts and things like that.

Q: Do you have a book that you could recommend that you think no one will have heard of?

A: Oh, that's difficult. Well, I just got this one from a friend and I started reading it and it's called The Oceans of Cruelty: Twenty-Five Tales of a Corpse-Spirit by Douglas J. Penick. It's a sequence of 25 tales from India whose central themes are the dark power of storytelling. The protagonist promises a young yogi, I think, to bring a corpse spirit that hangs upside down from a tree and it's a malevolent spirit. And night after night, there's a new story. It's like the very classical one story every night, like Arabian Nights, but from Indian tales. It's the retelling of Douglas J Penick though because I think these are traditional stories that might be really, really difficult to get around. I think this is a little treasure that a friend gave me the other day and so far I’ve only read only 3, but I was spooked and I’m usually not spooked.

Q: Do you have a favourite story from this latest collection?

A: I think ‘Different Colors Made of Tears’. It's the story of the girls in the vintage shop with the clothes when the clothes are like a second skin. And I really wanted to talk about this. It was a very familiar space, and a space that I found very safe in many ways because I like buying vintage clothes. But at the same time, those clothes have a history, they have an owner and they are a bit haunted in a way. Even when you go into a vintage shop, the smell is particular. So I was thinking about that for a while and I was like, ‘what if those stories are in the clothes?’ Since you put them on your body and it’s so near and intimate, what happens? And there are many stories like that, but I tried to do it with a twist that was a bit more brutal or explicit.

Q: Do you have anything that you're working on next that you can tell us about?

A: I’m working on two novels in the way that I’m writing one and the other one is growing up, and I should probably stop that other one from growing up because it’s going to be a disaster. And then two nonfiction books, one about the history of my readings and the other one is the second part of my book on cemeteries and travels to cemeteries. This is insane, but anyway, I can’t stop doing it. I’m looking forward to a long vacation of just not talking, not touring and just writing.